St Martin’s Conservation TrustTrust dé Consèrvâtion d’Saint Martîn

Background Information

The St Martin Conservation and Development Plan was drafted by a committee set up by the late Stanley de La Haye, Connétable, at the invitation of the (then) Island Development Committee in 1989. This plan was approved by the States of Jersey in December 1993. Paragraph 2.2 stated ‘That a St Martin Conservation Trust be set up to encourage conservation and to initiate enhancement schemes in the Parish’.

The Connétable and the Comité Paroissial discussed the concept and decided that such a Trust should be separate and independent of the Parish Municipality. The Parish Assembly of 16th April 1992 gave unanimous approval. In December 1992, the Trust was created as a charitable trust by individual parishioners with a keen interest in conservation under the chairmanship of the late Sir Robert Le Masurier, a former Bailiff and parishioner. The other trustees were: Martyn Chambers, Christopher Aubin and the late Major Maurice (Mike) Lees. Mike Lees served as Hon. Secretary and Treasurer from 1992 to his retirement in 2009.

The formal aims were to promote and assist in the protection and conservation of architectural, archaeological and cultural heritage, and the landscape, environment and buildings of historical and scientific interest in the Parish.

Trustees

On the death of Sir Robert in 1999, T.R. de Gruchy (Procureur du Bien Public) was elected as Chairman. He resigned in 2002 and G. P. Le Cocq (then Procureur du Bien Public) was elected in his place. Deputy Steve Luce attended the meetings until he became Minister for Planning and Environment in 2014, after which he stepped down.

The current trustees are G. P. Le Cocq (Hon. Chairman), Antony Gibb (Hon. Secretary), Mary Billot, Paulette de la Haye, Anne Holden and Claire Du Heaume.

The trustees meet regularly and carry out a range of different activities including monitoring planning applications. The Trust comments if applications affect (a) listed buildings; (b) the coast either within the Coastal National Park or deemed to be prominent when seen from the sea; (c) the rural environment either agricultural land or rural lanes.

Other projects have included the sponsored tree planting on the Village Green and parish car park, and the production of a Guide to St Catherine’s Bay. The text of this guide is now on the parish website.

St Martin Parish Treasure

The commitment of the Parish to its environment was exemplified by the production of the St Martin Parish Treasure in 1980 to 1982, which was compiled by the late W.B. Gibb (1920-1992). Mrs Joan Stevens (1910-1986), a president of the Société Jersiaise, wrote two influential books on Old Jersey Houses, which were published in 1965-1977. Brian Gibb soon realised the value of such research so he and his wife the late Mrs Mary Gibb asked her to come to their home at Les Grandes Rues, Faldouet; they quickly became friends.

Mrs Stevens wanted to extend the knowledge of buildings of interest in each parish so she found people who would construct a survey to be known as ‘The Parish Treasures’, which would be kept in each Parish Hall. One of Brian Gibb’s aims was to have a source of information that the Planning Department would have to check before passing or stopping plans going ahead. The photographs were taken by Brian Gibb and Michael Richecoeur. It is believed that the St Martin Parish Treasure was the only one to be completed in this form.

One copy of the record is in an album at the Public Hall; the Planning Department deposited the only other copy (in two folders) at the Jersey Archive (Collection ref. F/G/H5/1).

As of July 2016.

Contact Details

Contact with the Trust is c/o the Public Hall, Rue de la Croix au Maître, St Martin, Jersey JE3 6HW. T: 01534-853951, E: [email protected].

-

ST MARTIN PUBLIC HALL

There is a succinct history of the Hall in the parish’s Millennium history – St Martin Jersey : the story of a parish; edited by Chris Blackstone and Katie Le Quesne Phillimore, 1999.

The book was scanned in 2021 and was loaded onto the Parish website. It is available on the Home Page under News & Events then click on ‘St Martin – the story of an Island parish’. It is the only parish history to be accessible in this form, for which St Martin can be proud.

In 1806 General Don decreed that each parish should have a drill shed. One of the maps accompanying Jersey place names (Société Jersiaise, 1986) shows our old drill shed on the corner of La Rue des Raisies and La Rue de la Croix au Maître. It has long gone under tarmac and road widening.

In 1877 these parish drill sheds were abolished as most of them had fallen into disrepair. This prompted the States to offer each parish £200.00 to build a Parish Hall. In St Martin, a Parish Assembly was convened at the Crown Hotel to discuss the matter. This hotel later became a shop and private house. The shop is now Landes Interiors, and the private house remains.

The Connétable was instructed to invite tenders for a two-storey building. The Parish was not satisfied with these tenders so nothing happened. I assume that the Assembly was not prepared to augment the States grant with parish money. Ten years passed (quite rapid given Jersey’s sloth in some building projects) and 1887 is reached. Then the Parish received an offer of £75.00 towards the cost; this came from the Rector, the Reverend Thomas Le Neveu. He was the second husband of Emilie Chapman, the widow of Capt. Henry Pitcher VC. She was instrumental in getting the Pitcher memorial window installed in the Church.

The money had been given by friends of the St Martin Church Sunday School toward the cost of building a public hall on condition that the Sunday School could use it on Sunday mornings.

The Church did not (and still does not) have a Church Hall. As a result St Martin is the only parish to have a Public Hall rather than a Parish Hall and it makes sure that everyone knows of this difference. Of course St Helier has a Town Hall.This donation in 1887 obviously galvanised the Parish to do something; other parishes had taken up the States’ offer and already had their parish halls built. So St Martin was very dilatory in getting something done. The architect was Hammond Rush and the estimated cost was £300.00. The scheme was eventually adopted resulting in the modest nature of the original building, compared with those elsewhere. In the past 120 years it has been refurbished and extended several times.

In April 1954, instigated by Connétable Henry Ahier, a Parish Assembly approved plans to provide administrative offices costing £2,233.00. In 1971 the offices were again extended under the term of office of Connétable George Le Masurier, adding on the centeniers offices and one for the Connétable himself. In 1987 the hall floor collapsed when the leg of the piano fell through it. So repairs were needed; the hall and the committee room behind the stage were totally refurbished. It was re-opened by Sir Peter Crill, Bailiff of Jersey, in 1988.

More improvements were needed when the main office was renovated in 1991 (Connétable Stanley De La Haye). In 1997, Connétable John Germain authorised another office extension and the redecoration of the hall. This entailed three offices for the honorary police, a toilet for the disabled and a small kitchen. The roof space provided two large committee rooms with dormer windows. This time the cost was £180,000, 600 times more than the cost of the original hall. Sir Philip Bailhache opened the building in 1997.

Like other parish halls, the walls are embellished with photographs of past Connétables. There are three large oak boards recording their names (starting in 1490), and a small oak board lists the Deputies from 1857 (donated by me in memory of my parents and grandparents). There is also a Parish tapestry embroidered by parishioners at the same time as the Occupation tapestries displayed at the Occupation Museum (1995); other photographs and mementos are also on the walls. The large collection of centeniers’ and vingteniers’ batons are displayed elsewhere in the building.

The building covers a wide range of functions, which would have astonished the local militia users of the old drill hall. There is the parish administration, community functions (eg. Les Nouvelles de St Martin), all sorts of licences (eg. driving licences), everything to do with elections, and news and events. Then there are the Parish Assemblies, Public Hall enquiries, rates meetings, and ‘government’ presentations on Island Plans or the new hospital. It is not clear how the 2022 election hustings will go ahead in the new constituencies.

Mary M Billot

31/03/2022 -

Parish History

The parish of St Martin has an area of 9.9 square kilometres and includes the archipelago of Les Ecréhous, which are only seven miles from the coast of Normandy. St Martin is a mainly rural parish with an extensive network of green lanes. It has retained a strong sense of its own identity and its parishioners defend its beauty and tranquillity with vigour. The coastline is magnificent with steep cliffs, harbours, sandy beaches, paths and the huge St Catherine Breakwater. The north-eastern coastal areas between Rozel and St Catherine’s Bay are designated as an Area of Outstanding Character in the new Island Plan. The main clusters of population are in St Martin village, Gorey, Maufant and Rozel.

The area has a rich prehistory, which includes two important megalithic monuments originally buried beneath mounds of earth and rubble. They were both built to the same orientation, 19 degrees south of east. A local clergyman excavated them in 1868 and sadly sold some of the finds. The gallery grave of Le Couperon (about 2500 BC) is off La Rue des Fontonelles; it is a long-cist constructed from the local Rozel Conglomerate stone; Philippe Falle first recorded its existence in 1734. The passage grave of La Pouquelaye de Faldouet, off La Rue des Marettes is dated between 4000 and 3500 BC; some of its stones came from the Mont Orgueil and Anne Port area. It was first excavated by its then owner in 1839 and was last reconstructed in 1910.

Guide to St Catherine’s Bay

St Catherine’s Bay faces east and lies between Verclut Point and La Crête. It takes its name from the lost mediaeval chapel of Sainte Catherine, between La Route Le Brun (the Pine Walk) and La Rue du Champs du Rey, at Archirondel.

The bay was an important centre for shipbuilding and many parish families were involved. The first recorded ship, the Laurel, a 16 ton cutter, was built in 1824 and one of the last was the St Catherine, a 107 ton schooner built in 1877. The duty free timber was imported from northern Europe and the industry was at its zenith in the 1860s. Then sail gave way to steam and wood made way for ships of iron, which needed more capital investment than local shipbuilders could provide.

Vraic (seaweed) is a natural fertiliser, which has been used for centuries to improve the land. The bay still provides local farmers with seaweed torn from the rocks by the action of the waves; it is no longer harvested with a sickle. It contains valuable trace elements and calcium, all lacking from the local soil.

Before the Reformation, the parish had many chapels. The sole survivors are the Parish Church, Rosel Manor chapel and the crypts at Mont Orgueil Castle. The Parish Church is dedicated to St Martin de Tours, and is first recorded in a charter of 1042. The seigneurial chapel at the Manor is 12th century and is a surviving part of the original manor, with the fishponds and the colombier (pigeon loft). The mediaeval chapel of Ste Agathe was at the foot of Le Mont des Landes. A 15th century granite cross stands at the lifeboat slipway at St Catherine and another one is embedded in the roadside wall of Wrentham Hall at La Croix on La Grande Route de Rozel. The granite millennium cross for 2000 AD is at the foot of Mont des Landes on the Route de la Côte.

Rosel Manor is one of the five senior fiefs of Jersey; once a year the Seigneur of Rosel swears an oath of allegiance to the Crown at an Assize d’Héritage. The fief also has the right to make homage to the Sovereign on arrival in Jersey. It is still owned by the Lemprières, who trace their ancestry back to 1367, when Raoul Lemprière was the first of his family to live in Jersey. Its feudal gallows were on Mont Daubignie. The present manor was built in 1770 as a Georgian granite house; in 1820 it was encased in concrete with new gothic-style turrets. The manor is not open to the public.

Defending our Coast

Mont Orgueil Castle is in St Martin; it is Jersey’s most famous symbol and its distinctive silhouette towers above Gorey Harbour. It is a magnificent example of mediaeval military architecture built on a promontory first occupied in the Neolithic era. When King John lost continental Normandy in 1204 to King Philip Augustus of France, Jersey remained loyal to the English Crown and became a frontier outpost within sight of the enemy. It had to be fortified against enemy attacks, as Carteret (Normandy) is only fourteen miles away. So a bow and arrow castle was built, which became the seat of island government in the 13-15th centuries. It was continually upgraded up to the days of cannon, after which it fell into disrepair. Sir Walter Raleigh, Jersey’s Governor at that time, saved it from demolition in 1600 and it was used as a prison and garrison in the 17th and 18th centuries. In 1907 the Crown transferred it to the States of Jersey and it became a tourist attraction. It was a self-contained strongpoint during the German Occupation.

Because of its strategic position in the Bay of St Malo, Jersey had to defend itself from French invasion for over six hundred and fifty years. The Plantagenet kings held sway over Anjou, Aquitaine and Gascony and Jersey was crucial in the protection of the coastal wine trade from those areas. The English kings appointed Wardens of the Isles who were based at the Castle; even so the island was subject to raids by pirates, occupation and pillaging throughout the 13th century. The year of 1294 was particularly devastating; the castle held out against the French but the countryside was burned and looted. After this, Edward I funded the further strengthening of the castle.

The Hundred Years War with France started in 1337 and ended in 1453; Edward III had become king in 1327 and by 1337 felt secure enough to pursue his claim to the French throne. Once again Jersey was in the firing line and had to take steps to defend itself. The islanders manned the garrison and each parish was obliged to form trained militias of archers, cross-bowmen and other men-at-arms. In 1373 the famous French Constable of France, Bertrand du Guesclin, laid siege to the Castle but only succeeded in capturing the outer defences. He agreed to lift the siege after payment of a ransom and the surrender of hostages. The war simmered down and Jersey began to prosper with the increasing safety of travel. Building continued at the Castle throughout the 14th and 15th centuries.

However Jersey’s peaceful respite was brief because the Wars of the Roses started in 1455; the island was divided by Yorkist and Lancastrian family feuds even though the conflict for the throne was far away in England. In 1461 the castle was betrayed to French supporters of the Lancastrians; they ruled Jersey for seven years before they were driven out by Sir Richard Harliston, the Yorkist Admiral of the Fleet. There was now a lengthy period of peace and the castle gently decayed.

The next great spurt in fortifications began in 1778 when Bourbon France allied itself with the emergent American colonies and declared war on England. After an attempted invasion by the Prince of Nassau, the defence of the island was reorganised. Another invasion of 1781 was repulsed at the Battle of Jersey; this galvanised the building programme, which included earthworks for batteries, bulwarks and guard-houses. General Conway, the Governor, ordered the building of a series of coastal towers; they had interlocking arcs of fire covering the likely sea approaches. These distinctive structures were precursors of English Martello towers. The ones at Fliquet and St Catherine were completed by 1787; the Archirondel example was more elaborate with a gun platform and was finished by 1794.

By now the threat from the Revolutionary regime had replaced that from the Bourbon kings. At first England observed neutrality but the declaration of the French Republic in 1789 and threat of further revolution drew her into the European conflict and once again she was at war. Jersey was a military garrison from 1796 until the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. Officers and men were stationed at Mont Orgueil and artillery and the local militia were deployed at the towers.

This was the golden age of Jersey privateering whereby the Crown licensed local shipping to capture enemy ships. Whenever war broke out, ship owners mounted some guns on their vessels and applied for Letters of Marque, whereby their ships became auxiliaries of the Royal Navy. During the Seven Years War (1756-1763) privateers caught prizes worth £60,000, and in the War of American Independence on one occasion more than 150 French ships were anchored in St Aubin’s Bay. By the Napoleonic Wars the French were more heavily armed and Jersey lost two thirds of its shipping. But the surviving third made large profits and some local families became very wealthy.

There was more tension in 1830 when Louis Philippe ousted Charles X from the French throne. Defences were again upgraded to cater for the improvements in naval firepower. In 1837 the Victoria Tower was built on the headland above Anne Port. The single 32-pounder gun on its platform would have been capable of covering the southern approach of the harbour of refuge being planned in St Catherine’s Bay.

St Catherine’s Breakwater

Building the Breakwater started in 1847 and work on it finally ceased with the completion of the masonry in 1855. The British Government commissioned this huge Victorian engineering project to serve as the northern arm of a proposed harbour of refuge for the Royal Navy in times of war. It is over 700 metres long and cost more than £234,000. The southern arm at Archirondel was never completed; only a stumpy pier exists. The French enlargement of the naval port of Cherbourg and the fortifications at St Malo and Granville prompted the project.

The whole enterprise was a complete waste of money because the advent of steam ships made harbours of refuge redundant. The Government then hoped to sell to the States of Jersey the Breakwater and other local buildings, which it had acquired to house its managers and the workers’ hospital. After twenty years of financial negotiation and continual stonewalling by the States, it transferred ownership as a direct gift, which was finalized on April 12th 1878. The Breakwater is now used by anglers, boat owners and by people exercising themselves and their dogs.

Two large pieces of stone mark the start of the Breakwater. The Rozel Conglomerate rock boulder was laid down about 500 million years ago and is nicknamed the Pebble; the new granite parish millennium stone was erected in 2000 AD. The lighthouse at the end is a modern replacement dated 1973; you can see the original cast-iron tower of 1856 outside the Maritime Museum in St Helier.

Since 1969, the Royal National Lifeboat Institution has stationed an inflatable lifeboat at St Catherine. In 1990 a new lifeboat station came into service, built near the St Catherine’s Tower (the ‘White’ Tower) and local volunteers form the crew.

Marine Life

Jersey’s greatest natural treasure is its forty-five miles of coastline. The areas between the high and low water mark surrounding the island have remained relatively unchanged in the last few millennia; by about 4,000 BC the sea had risen sufficiently to drown most of the land between the islands and the French coast. Our seashore is subjected to dramatic change every six hours because of its unique position in the Bay of St Malo. Huge areas of marine habitat are exposed at low tide. Over spring tide periods, the tide can rise and fall over thirteen metres twice a day. So everyone needs to take great care not to become cut off by the rapid incoming tide if they are exploring the marine habitats between the high and low water marks.

We have a great variety of marine life on our seashores and in the shallow seas that surround us. There are well over 100 species of fish, 80 species of worm and 100 species of crustacean. Our seaweeds (vraic) are also very varied with 30 species of green, 60 species of brown, and 140 species of red seaweed. Vraic is a natural fertilizer and contains valuable trace elements and calcium, which has been used for centuries to improve the land. The bay still provides farmers with vraic; it is now harvested with a tractor rather than with a sickle. Look out for crab and razor fish shells, cuttle fish skeletons, dead jellyfish and a great variety of seashells amongst the marine litter on our beaches.

The island is almost the most southerly part of the British Isles and so summer temperatures are usually higher here than elsewhere around Great Britain. Our clean and constantly flowing water is a fine habitat for species rare further north. We are lucky to have sightings of large groups of bottle-nosed dolphins on the east coast. It is thought that our local population of these popular sea mammals is one of the largest in the British Isles.

Jersey people are keen fishermen and many set crab and lobster pots off shore, marked by their owners’ buoys. The local edible crabs are spider and chancre crabs. Low water fishermen look for shrimps, prawns, razor fish and limpets in their favourite places. You will often see fishermen along St Catherine’s Breakwater hoping to catch monkfish, mackerel, and plaice on an incoming tide. Bass is a prized catch from the deeper waters.

The Channel Islands are on the absolute edge of the warm water habitat for the ormer, a highly prized local mollusc. Its Latin name is Haliotis tuberculata but its common name is abalone, mutton fish or sea ear. The ormering season runs from September to April (when there is an ‘r’ in the month) and only those of sufficient size can be harvested, in order to preserve stocks. They need very slow cooking to tenderise them.

The conger eel is another local sea creature; it can grow up to seven or eight feet. You will see them for sale in the St Helier fish market. Conger eel pie and soup are typical Jersey dishes; marigold petals are considered to be an essential ingredient for the soup.

Natural History

The hospitable climate and varied landscape of the north-east coastline of Jersey provides a welcoming environment for many species of birds and animals. Some are not usually found in the British Isles and others are seasonal visitors from nearby Normandy. When the right winds and weather conditions prevail, honey buzzards may easily slip across the short stretch of water.

The rich and beautiful area of St Catherine’s Woods is one of the most extensive natural environments open to the general public; the watercourse cuts a delightful valley through the escarpment. Many songbirds can be seen and heard particularly at dawn in May : song thrush, blackbird, finch, tit, chiffchaff, collared doves and wood pigeons, and even the tiny short-toed tree creeper (the ‘mouse bird’).

The red squirrel was introduced by local naturalists in the 1890s and there is now a population of over 400. They are encouraged to spread by the planting of tree avenues so that the separate colonies can inter-breed.

They are seed-eaters and depend on the seasonal crop of acorns, beech nuts and sweet chestnuts to support them through the year; they collect and store these nuts as they ripen. However wood mice and voles often steal from their stores, so garden bird-feeders supply reserve rations. Predators such as hawks, barn owls and domestic cats prey on the young kitts.

The shoreline attracts all kinds of seabirds, whilst St Catherine’s Breakwater provides a vantage point to see small bottle-green cormorants (‘shags’) which nest along the steep north coast. Gannets feed on the shore from their colonies on Alderney’s off-shore stacks. Grey herons, oyster-catchers, turnstones and little egrets are seen sifting for food in the rocky gullies by the Breakwater. Look out for the sight of bottle-nosed dolphins, the island’s favourite sea mammal, which roam the local sea and often shadow sailing yachts.

Wild flowers and plants proliferate on the shore and in the woodland. Sea spinach grows along the coastal walk between Archirondel and St Catherine, and used to provide nutrition in past times. The Jersey fern is a rarity; it is a small annual plant which grows on the sides of rocky banks and benefits from our hot summers and mild wet winters. The ‘three-cornered leek’ or ‘stinking onion’ thrives in hedgerows and banks, with its white bells.

Other common plants are yellow flag irises in the meadows of St Catherine’s woods and the purple foxglove in spring. Winter heliotrope flourishes in winter giving out its delicate scent and the white spires of navelwort rise up from the fleshy rosette-like leaves in roadside banks.

-

By Mary Billot (St Martin Conservation Trust)

The Millennium Cross

To celebrate the Millennium in 2000 AD, the States of Jersey donated a millennium cross to each parish. This project was one of those sponsored by the Millennium Fund to mark 2,000 years of Christian faith. The design was based on the cross which now stands at Elizabeth Castle. It was erected there in 1959 to mark the site of the Abbey of St Helier and is believed to be an excellent reproduction of a mediaeval wayside cross. These would have been prevalent throughout Jersey until they were all but destroyed during the Reformation.

One surviving cross from the Chapelle de la Croix is embedded in the roadside wall of Wrentham Hall, on the Grande Route de Rozel, opposite La Rue Belin. There is also a well and a fishpond (le vivier), which would have provided fresh water and fish for the resident priest.

The twelve parish crosses are to the same design, differing only in the inscriptions which were determined by each parish. Our parish cross is at the foot of Le Mont des Landes, by the carpark on La Route Le Brun (B29), and is about eight feet tall. The slender granite cross is on top of a solid granite base with a supporting octagonal collar. The collar bears the parish crest and two inscriptions in gold lettering. Each cross cost about £1,000 (in 1999); the stone-dresser was Mr Michael Frost. He spent about a week on crafting each one.

One side of the collar states: To the north & south of this site were two 14th century chapels dedicated to St Catherine & St Agatha.

A second side states: Post-Reformation the two chapels fell into ruins and were demolished in 1844 during the building of the breakwater.

On the cross-piece is incised: TO THE GLORY OF GOD.

The granite base states: In the year of Our Lord 2000.

It is believed that the chapel of St Catherine (La Vieille Chapelle) was on the sea-shore near to Archirondel Tower; ruins survived until 1852 when the road to St Catherine’s Breakwater was built. It had its own cemetery. La Vieille Chapelle in La Rue des Champs du Rey may have been the site of its priest’s house. The chapel of St Agatha was also on the sea-shore north of the present Archirondel jetty; it was also demolished in 1852.

The Millennium Standing Stone

This initiative came from the Société Jersiaise in 1998 and was endorsed by the Comité des Connétables. All parishes were given a standing undressed granite stone, which was jointly funded by the Société Jersiaise and Ronez Quarries. Each stone was also accompanied by a marker stone with an explanatory bronze plaque, which was sponsored by Romerils Ltd.

These stones recognize pre-Christian beliefs which marked burials or other sacred sites with a menhir (a single standing stone of the Neolithic Age). Our stone is at the top of St Catherine’s Breakwater at Verclut (B29) and is about 2.5 metres high. Unfortunately its marker stone does not bear the requisite plaque. The Jersey Field Squadron delivered the stones to the parishes and helped to set them up in the chosen locations.

It had been hoped that a network of footpaths would link the stones, but this did not materialise. However they do feature in parish walks, when the guides bring them to the attention of walkers.

-

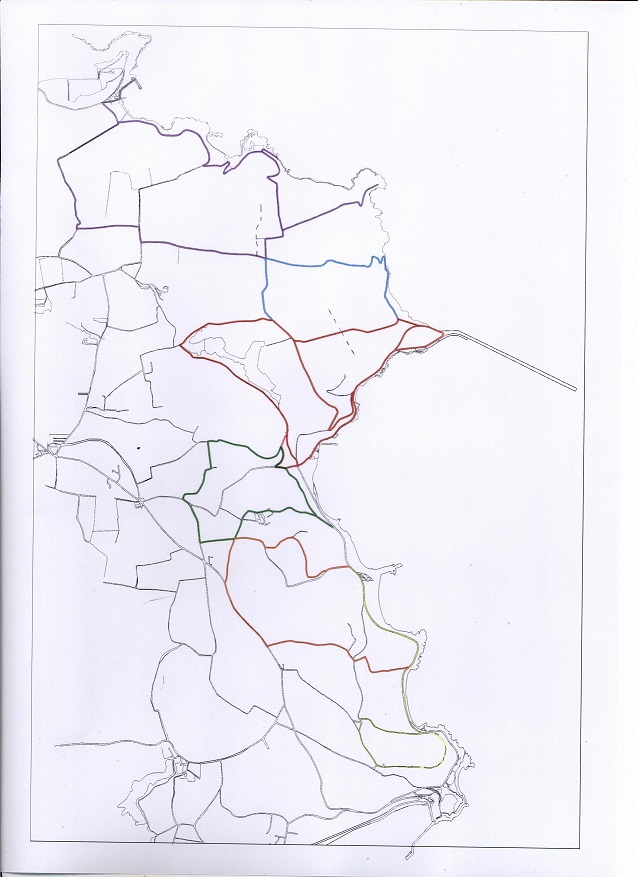

With thanks to Marc Medland for kindly supplying this map NO. 1. St Catherine’s Short Walk

Light blue on map. Park at Breakwater. Bus no.2

Starting at the café at the Breakwater, take the north arm of the circular road around the rock to the junction of the sea wall with the land; a footpath is indicated on the right. Follow the steep upper path (the lower one has been lost in a landslide) past the upright railway lines planted by the Germans as an invasion obstacle and go to the roadway at the end. Turn right, following the lane downhill. Or take the path through a copse of trees planted on the slope below the road. You will come to Fliquet slip and its tower, the first of its kind built in 1793.

Continue on this lane as it rises again, passing ‘Fliquet Castle’ built from shaped granite stones rescued from older buildings. After a farmhouse and cottages, you reach a crossroads. Turn left and follow the road past La Haie Fleurie and its flowering hedgerow until you come to a left turn. Pass some fine Victorian houses to reach the junction with the path which climbs from the Breakwater.

NO. 2. Rosel Woods North Circular

Red on map. Park at St Catherine’s Tower. Bus no.2

Walk left out of the car park and soon turn right at the cross roads. Almost immediately take the left fork onto a track which goes past the small reservoir built by the Germans. Cross the stream by stepping stones. Follow the path along the valley through the woods and meadows until you come to a junction which you can cross the stream on your right. Take this path which rises out of the valley between granite walls until you emerge from woods to fields, where Jersey cattle sometimes graze.

Continue to the crest; you will pass on your right a small copse of ancient pines where the Seigneur de Rosel would hold court and where the local gallows once stood. At the end of the path, join B91, when you may turn left to go down to Fliquet Tower (walk no.1) or right and then left to reach the Breakwater. The right turn descends with views of the bay as far Mont Orgueil Castle, reaching the crossroads from where you started.

NO. 3. Rosel Woods South Circular

Red and green on map. Park at St Catherine’s Tower. Bus no.2

As with walk no.2, take the path through Rosel Woods, but then go up the path which rises steeply to your left opposite the meadows. This takes you out of the woods onto a footpath hedged on both sides between fields to a junction where four lanes meet. The left path leads directly down the hill to your starting point.

However turning left and immediately right takes you along the crest to the top of St Catherine’s Hill (B62). Again turning left and then immediately right, you come to another road on the left. Turn left and left again into an attractive lane which leads to the Pine Walk (B29, La Route Le Brun). Turn left again and you will get back to the start point at St Catherine’s Tower.

NO. 4. Archirondel Circular

Yellow on map. Park at Archirondel Café. Bus no.2

Walk up to the main coast road (B29) and turn left. Take the next steep lane on the right which rises through the woods behind Les Arches apartments (La Rue des Viviers). At the top turn left following the crest to a complex junction above Anne Port. Descending here will take you down the coast road to Jeffrey’s Leap (Le Saut Jeffroy), where you can turn left to return to the start point.

Alternatively, turn right and then left at a T junction. On the right is the sign to the Dolmen de Faldouet, a Neolithic passage grave of 17 stones (Société Jersiaise). Keep straight along the crest; shortly there is a private lane leading to Mont de La Garenne, immediately opposite Mont Orgueil Castle. On this headland is Victoria Tower (National Trust for Jersey), built in 1836 to defend the southern part of the bay and the landward side of the castle. There are also defences built during the German Occupation for the same purpose. Below the Tower is a path which goes down to the coast road at Jeffrey’s Leap, which takes you back to Archirondel.

NO. 5. Rozel Bay, Le Saie Harbour, La Coupe, Rozel Bay (Circular)

Dark blue on map. Park at Rozel Harbour. Bus no.3

Leave the Harbour by Rozel Hill (B38), climbing eastwards. At the top of the hill look out for a house on the right (Le Saie House). Beyond this house take a sharp left on to the sign posted footpath, La Rue des Fontenelles (the lane of little springs) The path twists and turns, drops into the little valley and then climbs to Le Dolmen du Couperon, the prehistoric burial site to your left. It is a long-cist, or allée couverte, first recorded in 1734 (Société Jersiaise).

Carry on downhill to the end of the Rue de Fontenelles. There is a small car park and a path to the left that leads to the main car park. This takes you to La Havre de Saie, which is an anchorage for small boats rather than a harbour. Go up the twisting narrow road and continue to the sharp left into La Rue de La Coupe. The road to the headland of La Coupe becomes steep; a guardhouse was built there to keep watch during the Napoleonic Wars. A small path on the right takes you to the beach.

Now retrace your route until you reach the T-junction. Turn left into La Rue des Scez, which twists right then left to a crossroads. Turn right into La Rue des Pelles, passing Rozel campsite on your right. At another T-junction turn right then left into La Rue de Caen. You are going downhill towards Rozel Valley; at the T-junction turn left and keep going down. Watch out for the local red squirrels and note the granite gutters by the side of the road. Some of the houses on either side of the valley have granite date stones. The road curves to the right and you will see some magnificent trees on both sides, which thrive in the bay’s sheltered microclimate. Pass the Chateau La Chaire Hotel and Rozel Bay is ahead of you.

NO. 6. Archirondel to Anne Port

Orange on map. Park at Archirondel Café.

Walk up to the coast road and turn right. Take the first turning on the left; the St. Martin’s Parish Millennium Stone is on the right hand side of the coast road. Half way up the hill (Mont des Landes) turn right into a small lane called La Vielle Charrière. Follow this lane up hill to the north and then west. There are fine views on the right across fields to the sea at St. Catherine’s Bay. Where the lane rejoins the Mont des Landes, turn right again. At the first cross roads turn left into Rue de Basacre, which soon joins the Grande Route de Faldouet.

Turn left following the road until you reach a lane on the left, which has one of the longest names in Jersey: La Rue de Guilleaume et d’Anneville. Follow this lane, passing two beautiful old farmhouses on your left. After passing Anneville Farm on your right, take the next turn left into a narrow lane called Mont de la Crête. This will take you steeply down to the Route de la Côte at Anne Port. Here turn left and follow the road round the headland to Archirondel Bay and back to the car park.

Vessels in Gorey Harbour

As enumerated in the censuses from 1861 to 1901 information researched by Mary M. Billot.

Definitions –

- Cutter – single mast; fore and aft rigged

- Ketch – 2-master. Fore and aft rigged; aft mast shorter than fore mast

- Dandy – sloop-like vessel with jigger mast behind

- Sloop – single mast; cutter rigged

- Smack – single mast; small decked or half-decked coaster or fishing vessel rigged as a cutter

Please click here to view the full list of vessels recorded on each census and their tonnage.

-

Captain Henry William Pitcher, Victoria Cross (1841-1875)

Henry William Pitcher was the second son of St Vincent Pitcher, an officer serving in the 6th Madras Light Cavalry, and Rose Mary Le Geyt (1816-1901), the daughter of Admiral George Le Geyt CB (1777-1861). He was born in Bath, Somerset, in 1841 and his father died young. His elder brother Duncan George was born in Hyderabad, India in 1839, and died in Jersey in 1924, aged 84. The two sons were sent home to Jersey to continue their education. Henry William entered Victoria College in the autumn term of 1856 aged 15. The school was only three years old, having been founded in 1853. The headmaster at that time was Dr Henderson, a relative of Mrs Pitcher. At one time the Pitcher family had accommodation in Rozel Barracks.

Henry joined the Indian Army in 1857 and was commissioned Ensign; he set sail for India to arrive there at the height of the Indian Mutiny (1857-58) He was attached to the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders and served with the 79th Highlanders. He was promoted Lieutenant in 1858 and in 1859 joined the 1st Punjab Infantry, one of eight regiments that formed the Punjab Frontier Force. He gained his VC in October 1863 in the Umbeyla Campaign on the North-West Frontier, aged only 22. He was promoted to Captain but died of heatstroke aged 34, at Dehra Ghazi Khan, and was buried in the town cemetery. Because of flooding, he was later re-interred in Dehra Ismail Khan Cemetery, Kohat. The Umbeyla Campaign and the lengthy citation for the award of the VC have been fully documented.

St Martin’s Church has a stained glass window in his memory in the South Aisle, erected by his widow. She was Emilie Selina Augusta Chapman (born in 1843 in Ireland) whose second marriage was to the Reverend Thomas Le Neveu (born in St Clement in 1828), the Rector of St Martin from 1875 until his death in 1901. They married on July 7th 1887 in St Helier Parish Church; he was 59 and she was 44.

Captain Pitcher’s brother, Colonel Duncan George Pitcher had served as a lieutenant in the 21st Hussars and later became an officer in the Royal Military Artillery in 1856; he was promoted to Colonel in 1889. He retired to Jersey in 1896 and lived here until his death in 1924. He is buried in Green Street cemetery in the grave of his grandfather, Admiral Le Geyt. In 1867 he married Rose Elizabeth Evison of Greencliff, St Martin, at St Martin’s Church. She was born in Sunderland in 1840, the third daughter of J.C. Evison; she died in Lisbon in 1910. They had one son (1870-1914) and five daughters.

In 2008, Capt. Pitcher’s great great-niece, Mrs Anne Allen-Stevens, put his Victoria Cross up for sale as she wished to donate the proceeds to a UK charity Help for Heroes. This charity was formed to raise money to help service personnel injured whilst serving in Iraq and Afghanistan. Following representations from (Lieut. Colonel) Frank Falle of St Saviour, she withdrew it from Spink’s auction in London on April 24th 2008 so that the sum of £110,000 could be raised to purchase the decoration for the Island of Jersey.

This was successfully achieved in September 2008 and the money was transmitted to Help for Heroes via a locally formed charity Raising the Standard. On Sunday October 5th 2008, there was a short service of welcome at St Martin’s parish church for the medals’ arrival in Jersey. On Friday January 9th 2009 H.E. the Lieutenant Governor presented the set of medals to the Bailiff, Sir Philip Bailhache, for the people of the Island of Jersey, at a reception held in the Old Library, Royal Court Chambers. They are now in the care of Jersey Heritage.

Captain Pitcher’s medal entitlement forms a group of three: the Victoria Cross; the Indian Mutiny Medal (1857-58) with a ‘Lucknow’ clasp; the India General Service Medal (1854-95) with two clasps for ‘North-West Frontier’ and ‘Umbeyla’. The successful result of the fundraising to buy this group of medals means that all five Victoria Crosses with direct Jersey links are now in public ownership in Jersey.

References:

Mr Frank Falle (Raising the Standard)

Société Jersiaise Library

Jersey Evening Post, August 21st 2008

Spink catalogue, London, Thursday 24th April 2008, lot 106.

-

Mary M. Billot (St Martin Conservation Trust)

Introduction

Samuel Curtis (1779-1860) was a horticulturalist and plantsman, who designed and built the first garden at La Chaire. He is the personality mainly associated with La Chaire, because of his long life and fame as a plantsman. A later influential owner was Charles Fletcher (1870-1907) whose tenure was much shorter; he bought the garden in 1898 and died in 1907. Charles Fletcher’s influence on the garden has been overlooked because he was a peripatetic owner who owned it for only nine years until his early death. So he did not live long enough to enjoy his garden.

These two major personalities in the creation of La Chaire was the subject of a research monograph by Stephen Harmer, MA, called La Chaire: the story of Jersey’s lost garden, published by Seaflower Books in association with Hadlow College, Kent, in 2014. Mr Harmer dedicated his book to Charles Fletcher, and it is the main source of information for this short article. It is still in print and can be purchased locally. There is also information on Château La Chaire on the Historic Buildings Register maintained by the States of Jersey Planning Department, which can be searched on gov.je/Planning.

Samuel Curtis (1779-1860)

The life and career of Samuel Curtis is well documented. He was born in 1779 in Walworth, London; his family were Quakers whose roots were in Alton, Hampshire. In 1801 he married a cousin, Sarah Curtis (1782-1827), whose parentage is unclear. It is believed that she was the daughter of William Curtis (1746-1799), a cousin of Samuel. William was the author of Flora Londiniensis and the founder of the Botanical Magazine. Sarah inherited the Magazine when her father died, so Samuel became the co-proprietor on his marriage. The marriage was a happy one and resulted in 13 children, three of whom lived in Jersey.

Samuel had a very successful career as a plantsman and horticulturalist in Walworth, and later in Glazenwood in Essex. He was also a member of the Linnaean Society and a friend of Sir William Hooker, Director of the Royal Botanical Garden at Kew. After the death of his wife he came the sole owner of the Botanical Magazine which he renamed the Curtis Botanical Magazine.

By 1841 when he was over sixty, he was thinking about retiring. He also wished to cultivate exotic plants, which was not feasible in Essex. This brought him to Jersey where he hoped to grow sub-tropical plants from the Mediterranean, Australasia and South Africa. He was attracted by Rozel’s micro-climate and the local bedrock, the Rozel conglomerate, a pudding-stone found only in the north-east of Jersey, including St Martin. So in 1841 and again in 1844, his widowed daughter, Mrs Harriet Fothergill, purchased two areas of land from Thomas Machon. At some point her father started to build a house for Harriet and himself. This house was modest and stood at the bottom of the valley on the north side of La Vallée de Rozel. The current hotel (Château La Chaire) is Edwardian in the Arts and Crafts style, and was built by Charles Fletcher.

The sunny, sheltered, rocky valley is virtually frost-free as it is close to the sea. The original garden was terraced and was the home of an impressive collection of sub-tropical plants, many of which were imported from the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. With his daughter’s support, the garden became famous and Curtis enjoyed showing visitors around even in his old age. After his death in 1860, Mrs Fothergill and two of her siblings continued to maintain the garden as it matured. All four are buried in St Martin’s cemetery: Samuel (died 1860), his daughter Sarah Maria, who inherited the Botanical Magazine (died 1873), his son William (died 1887) and his daughter Harriet Fothergill (died 1888). None of the three siblings had any children.

Mrs Fothergill’s heir was a niece, Mrs Phebe Rooke, a widow; she was chaperone to Ka’iulani, crown princess of Hawaii (1875-1899) and seems to have been a relative by marriage. The princess’s father was Archibald Scott Cleghorn, who was a keen creator of gardens. Mrs Rooke and her charge visited La Chaire on four occasions from 1892 to 1897. The garden was devastated by a blizzard in 1895 which destroyed many of the tropical plants, an event which Samuel Curtis never imagined could happen as he assumed that his valley was a frost-free location.

Charles Fletcher (1870-1907)

After lengthy negotiations, Mrs Rooke sold La Chaire to Charles Fletcher in 1898. The garden now took on a new lease of life under this owner, who was a completely different personality to Samuel Curtis. Fletcher was born into a wealthy land-owning family of West Sussex, whereas Curtis was very much a self-made man with useful family connections. Fletcher was due to inherit the family estate and considerable fortune but made a disastrous marriage which affected the rest of his life. He married Ethel Beddoes, a Gaiety Girl, in 1895. She might have been accepted by the Fletcher family but for one insurmountable fact – she had an illegitimate son, called Charles Fairlie Cunningham, who was being reared by two aunts. The Fletchers refused to sanction the marriage and so Charles Fletcher was cut off from his inheritance with a one-off payment of £64,000 (about £2.5 million) and an embargo on Ethel Fletcher ever visiting the family estate.

So the Fletchers started a married life of travel and financial extravagance. Fletcher bought a yacht which sailed between England, France and Jersey but it is not clear as to why he settled on living in Jersey. However his diaries record the inspiration for the development of La Chaire: La Mortola, a garden in Bordighera, Italy, owned by Mrs Thomas Hanbury. Soon he was employing teams of builders and gardeners to build his house (now Château La Chaire), design his garden, and sort out drainage and access to a water supply. His engine-house for pumping water up to the garden’s water tank still survives on La Vallée de Rozel.

Planting started in 1899 with huge orders being placed with English plant suppliers. The Fletchers wintered in the south of France but Fletcher was constantly writing to his head gardener and builders about the completion of the work. Magnolias planted by Fletcher in his ‘new’ garden thrive at Magnolia Cottage, a later building. Because Fletcher kept on changing his mind and did not stick to an overall plan, costs were rising with consequent bank borrowings. However he continued planting, particularly roses, peonies, bamboo and delphiniums.

Fletcher was a heavy drinker and he recorded signs of liver disease in his diaries, which killed him in 1907. The garden was still subject to alterations so he and Ethel never saw it wholly completed. Their only child was Charles Hugh Fletcher, who sold the property to Mr Edward Roberts in 1921. It then passed to Mr and Mrs Arthur Nicolle in 1932. During the German Occupation, many of the plants planted by Fletcher and Mrs Nicolle, a keen gardener, were apparently sent to a botanical garden in Germany. From 1947, La Chaire has had a succession of owners. The garden infrastructure remains but most of the original planting schemes of Curtis and Fletcher have gone.

-